The Municipal Corporation of Gurugram (MCG) and the Municipal Corporation of Manesar (MCM) have adopted artificial intelligence (AI) tools to increase efficiency in property tax collection. Both civic bodies have reported significant gains since deploying AI systems that help identify defaulters, automate taxpayer communication, and resolve payment-related queries.

MCG has collected ₹200 crore in property tax so far in the current financial year, which accounts for roughly 72% of its ₹275 crore target for FY2025-26. In July alone, ₹95 crore was collected, attributed to the ramp-up of the AI-based intervention. The system was implemented under the leadership of MCG Additional Commissioner Yash Jaluka, who oversaw the integration of AI tools to improve revenue operations.

The civic body began by analyzing self-certified property data, identifying accounts with the highest outstanding dues. A generative AI chatbot was then used to contact property owners. The system categorizes users based on their payment behavior and customizes interactions accordingly. It also enables real-time responses to residents' queries, allowing a more targeted and efficient engagement strategy.

In Manesar, MCM Commissioner Ankush Sinha led the adaptation of this model. The initiative builds on an earlier pilot conducted in Yamunanagar, where Sinha had served in a similar administrative role. Since introducing AI tools, MCM has already matched last year’s property tax revenue of ₹29 crore within the first few months of FY26.

The approach taken in Manesar mirrors that of Gurgaon. AI technology classifies defaulters into sub-groups such as those willing to pay, those with valid difficulties, and those showing reluctance to comply. Each category receives a specific communication strategy, increasing the likelihood of recovery. In both jurisdictions, officials observed a marked increase in compliance following the AI-driven outreach.

The use of AI is part of broader efforts to digitize civic functions and improve governance outcomes. These systems are designed to reduce the need for manual follow-ups, increase collection speed, and ease the process for residents through automated assistance.

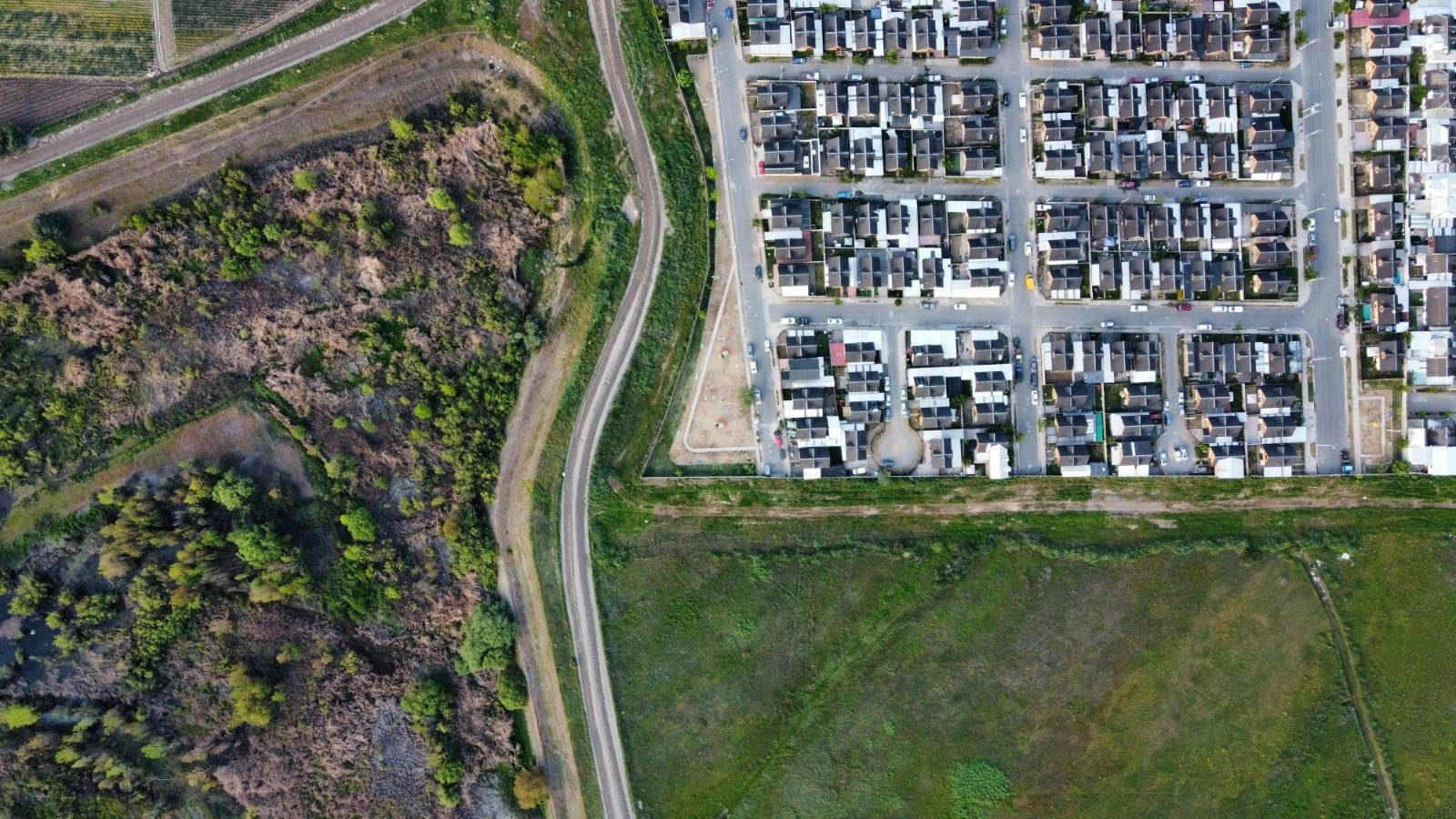

While the revenue performance has improved, questions have been raised about how the funds are being used. Residents like Gauri Sarin, who convenes the civic group Making Model Gurugram, have noted the disparity between increased collections and visible civic improvements. Sarin has pointed to gaps in urban infrastructure, manpower, and the availability of operational machinery. She emphasized the need for MCG to align its spending with service delivery benchmarks set by other high-performing municipal bodies.

The successful implementation in Gurgaon and Manesar suggests that similar models may be replicated across other municipalities in Haryana. AI is increasingly being viewed as a tool not just for efficiency, but also for enhancing financial sustainability in urban governance.

With this development, MCG and MCM join a growing number of Indian urban bodies experimenting with smart technologies to improve civic performance. Whether these systems lead to sustained long-term improvements will depend on how effectively increased revenue is converted into infrastructure and service delivery on the ground.